Pieter se gunsteling comic? Die Simpsons... en nou het dit blykbaar intellektuele waarde ;-)

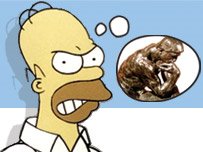

The Simpsons is more than a funny cartoon, it reveals truths about human nature that rival the observations of great philosophers from Plato to Kant... while Homer sets his house on fire, says philosopher Julian Baggini.

With the likes of Douglas Coupland, George Walden and Stephen Hawking as fans, taking the Simpsons seriously is no longer outre but de rigeur.

It is, quite simply, one of the greatest cultural artefacts of our age. So great, in fact, that it not only reflects and plays with philosophical ideas, it actually does real philosophy, and does it well.

How can a comic cartoon do this? Precisely because it is a comic cartoon, the form best suited to illuminate our age.

To speak truthfully and insightfully today you must have a sense of the absurdity of human life and endeavour. Past attempts to construct grand and noble theories about human history and destiny have collapsed.

We now know we're just a bunch of naked apes trying to get on as best we can, usually messing things up, but somehow finding life can be sweet all the same. All delusions of a significance that we do not really have need to be stripped away, and nothing can do this better that the great deflater: comedy.

The satirical cartoon world is essentially a philosophical one because it reflects reality by abstracting it, distilling it and presenting it back to us, illuminating it more brightly than realist fiction can The Simpsons does this brilliantly, especially when it comes to religion. It's not that the Simpsons is atheist propaganda; its main target is not belief in God or the supernatural, but the arrogance of particular organised religions that they, amazingly, know the will of the creator.

For example, in the episode Homer the Heretic, Homer gives up church and decides to follow God in his own way: by watching the TV, slobbing about and dancing in his underpants.

Throughout the episode he justifies himself in a number of ways.

"What's the big deal about going to some building every Sunday, I mean, isn't God everywhere?"

"Don't you think the almighty has better things to worry about than where one little guy spends one measly hour of his week?"

"And what if we've picked the wrong religion? Every week we're just making God madder and madder?"

Homer's protests do not merely allude to much subtler arguments that proper philosophers make. The basic points really are that simple, which is why they can be stated simply.

Philosophy's First Family

Of course, there is more that can and should be said about them, but when we make decisions about whether or not to follow one particular religion, the reasons that really matter to us are closer to the simple truths of the Simpsons than the complex mental machinations of academic philosophers of religion.

And that's true even for the philosophers, whose high-level arguments are virtuosi feats of reasoning, but are not the things that win hearts and minds. They are merely the lengthy guitar solos to Homer's crushing, compelling riffs.

However, being simple is not the same as being simplistic, which is one of the greatest crimes in the Simpsons' universe.

We can see this when Homer's house catches fire, in what could be seen as divine retribution for his apostasy.

But what actually led to the fire was not God's wrath but Homer's hubris and arrogance. Sitting on his sofa thinking smugly, "Boy, everyone is stupid except me," he falls asleep, dropping his cigar.

What really caused the fire was thus a slippage from the simple into the simplistic. Homer's mistake was to think that because the key points which inform his heresy are simple, that the debate is closed and he has nothing left to learn from others. But this is being simplistic, not keeping things simple.

Small dots, big picture

Revealing simple truths about simplistic falsehoods is not just a minor philosophical task, like doing the washing up at Descartes' Diner while the real geniuses cook up the main courses.

For when it comes to the relevance of philosophy to real life, all the commitments we make on the big issues are determined by considerations which are ultimately quite straightforward.

Pointillist paintings, such as this by Seurat, use thousands of tiny dotsA rich philosophical worldview is in this sense like a pointillist picture - one of those pieces of art in which a big image is made up of thousands of tiny dots (see Seurat image, right). Its building blocks are no more than simple dots, but the overall picture which builds up from this is much more complicated.

Yet we need reminding that the dots are just dots, and that errors are made more often not by those who fail to examine the dots carefully enough, but those who become fixated by the brilliance or defects of one or two and who fail to see how they fit into the big picture.

And the Simpsons certainly plays out on a broad canvas.

Any individual or group is shown to be ridiculous when only their pathetic and partial view of the world is taken to be everything. That's why no one escapes satire in programme, which is vital for its ultimately uplifting message: we're an absurd species but together we make for a wonderful world.

The Simpsons, like Monty Python, is an Anglo-Saxon comedic take on the existentialism which in France takes on a more tragic hue. Albert Camus' absurd is defied not by will, but mocking laughter.

Abstract themes

Another reason why cartoons are the best form in which to do philosophy is that they are non-realistic in the same way that philosophy is.

True heir to Plato, Simpsons creator Matt GroeningPhilosophy needs to be real in the sense that it has to make sense of the world as it is, not as we imagine or want it to be. But philosophy deals with issues on a general level. It is concerned with a whole series of grand abstract nouns: truth, justice, the good, identity, consciousness, mind, meaning and so on.

Cartoons abstract from real life in much the same way philosophers do. Homer is not realistic in the way a film or novel character is, but he is recognisable as a kind of American Everyman. His reality is the reality of an abstraction from real life that captures its essence, not as a real particular human who we see ourselves reflected in.

The satirical cartoon world is essentially a philosophical one because to work it needs to reflect reality accurately by abstracting it, distilling it and then presenting it back to us, illuminating it more brightly than realist fiction can.

That's why it is no coincidence that the most insightful and philosophical cultural product of our time is a comic cartoon, and why its creator, Matt Groening, is the true heir of Plato, Aristotle and Kant.

No comments:

Post a Comment